This June, Arctic Wild will be teaming up with Z-bird Tours for a rafting trip in the Western Brooks Range.  The Kugururok River is a great raft trip for many reasons. Our main reason for the trip is to find North America’s hardest to see bird. Recent reports of Gray-headed Chickadees on the Kugururok river, combined with Arctic Wild’s expertise in wilderness travel, and Z-bird’s phenomenal birding abilities, will make this, a trip wilderness birders will be talking about for years.

The Kugururok River is a great raft trip for many reasons. Our main reason for the trip is to find North America’s hardest to see bird. Recent reports of Gray-headed Chickadees on the Kugururok river, combined with Arctic Wild’s expertise in wilderness travel, and Z-bird’s phenomenal birding abilities, will make this, a trip wilderness birders will be talking about for years.

Here is what Z-Bird’s owner and guide John Puschock has to say about why he is excited to return to the area to get another look a Gray-headed Chickadee.

” Of all the resident bird species in North America north of Mexico, the Gray-headed Chickadee (a.k.a. Siberian Tit) is arguably the most difficult bird to see. It has a large range in the Old World, inhabiting boreal regions from Scandinavia to eastern Siberia. In the New World it inhabits only Alaska, Yukon, and the Northwest Territories. What makes it so difficult to see in North America is that there are almost no roads within its limited range, so just getting to where the birds are is an undertaking.

The Gray-headed Chickadee’s preferred habitat is a bit of an enigma. Various authors say it prefers spruce forest, others a mix of spruce and willow, or just willows. Even in the Old World, it’s preferences vary from region to region. In Alaska, it is usually found near isolated cottonwood (poplar) groves along a few north-slope rivers and in mixed scrub near tree-line in the Brooks Range It’s a cavity nester, often nesting in poplars.

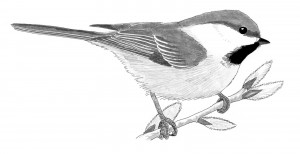

The Gray-headed Chickadee looks similar to Boreal Chickadee, but it’s bigger and has a larger white cheek patch and paler flanks. The Boreal Chickadee probably evolved from the Gray-headed during the Pleistocene glaciations, and it’s thought that the current New World population is actually the result of the Gray-headed re-entering North America following glaciations. Competition with the Boreal Chickadee may restrict its range.

Despite their close relationship, there’s no record of the two species hybridizing, which makes an encounter I had in 1998 all the more intriguing: The Kelly Bar on the Noatak River had for years, been the place to go to see the Gray-headed Chickadee, at least up until the mid-1990s. I was banding birds in Northwest Alaska all summer and I visited Kelly Bar intermittently. With each visit I expected to see Gray-heads, but two frustrating months went by with no sightings.

Finally in August I spotted a chickadee with large white cheek patches. “Finally”, I thought, but then I noticed that it was a colorful bird, as far as chickadees go. It’s flanks were more like a Boreal Chickadee, with warm tones. I froze and didn’t look for other field marks, such as white edging on the wing feathers (which would indicate Gray-headed). I was just trying to comprehend what I was seeing. And then all too quickly, the bird was gone. I saw it for only 30 seconds. If I actually saw, what I think I saw, it could have been a hybrid. But maybe it was a colorful Gray-headed, or a Boreal with more white in the cheek than normal, or maybe my eyes didn’t interpret things correctly.

After 12 years of pondering the brief encounter with the bird, it is time to return and take another look.”

Please join us in June for a fun filled birding adventure.