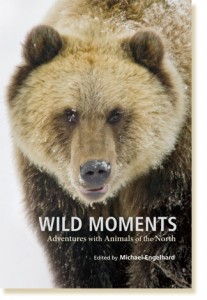

WILD MOMENTS: Adventures with Animals of the North

Edited by Arctic Wild guide, Michael Engelhard is now available.

Last August, on a nine-day backpacking trip I guided for Arctic Wild, we had a wolf walk right into our camp at Alapah Creek. My clients—a couple from Switzerland—were awed by the fact that you could just sit still and let a top predator come to you . . .

Aside from silence, solitude, open space, and the transcendent light, what keeps drawing many of us to high latitudes is the promise of a full deck of charismatic wildlife. Where else can you watch an entire hillside come to life as caribou follow their ancient call? Where else can you float serenely by grizzlies grazing on shore? Where else do distant boulders turn into musk oxen upon closer inspection?

After one such encounter, I got to thinking: what incredible stories of encounters with northern wildlife are out there, waiting to be told? I set out to find some of the best, and the result is Wild Moments: Encounters with Animals of the North, published last spring by the University of Alaska Press.

Below is an excerpt from the book’s introduction, describing the event that triggered the idea for the book. I hope it will revive treasured memories, help you through the cold, dark season, and whet your appetite for next summer.

* * * *

A few years ago I was guiding a backpacking trip in Alaska’s Brooks Range, an Arctic extension of the continent’s spine. One scene from that trek burned itself into my memory; unrivaled by other backcountry episodes, it keeps quickening like an ember when it is stirred. In less time than it takes to lace up my hiking boots, notions of invulnerability had turned to ashes. I was not, after all, exempt from Nature’s accounting.

During a layover in upper Joe Creek we struck out to bag one of the unnamed peaks that crowd the valley, or rather, to succumb to the view from the top, of range upon range marching toward the horizon. While we were crunching through gravel past hedgerows of willow, I chatted with the group strung out in the wash. Near a brace of limestone bluffs, belligerent coughing interrupted our footsteps and conversation. Bull caribou, I thought, as I scanned the slopes for movement.

For days we had tracked caribou along the ruts they braid into marshland, over passes, down broken defiles, fording streams fat with boulders, waist-deep in snowmelt or up to our kneecaps in mop-headed tundra, trying to get within optimal camera range, which meant close enough to hear the herd’s voice—its grunts, groans, and snorts a parody of arthritic men—or, closer still, what sounded like knuckle cracking: the tendons in feet that plied aufeis and scree and post-holed the boggy pits between tussocks with the efficiency of pistons. In the migration’s wake we had stalked wildness. Next thing we knew, it came barreling down at us from a ridge—huffing, jaws snapping, ears flattened.

“Cub and two sows,” I called out to my clients. My mind somersaulted, scrambling language. A female grizzly, a blond bulge of muscle and fur, rippled downhill with twin teddy bears in tow.

Following my lead, the group scuttled up the embankment, determined not to panic or turn their backs to the bear. We then stood and faced carnivorous disenchantment. As I fumbled with the pepper spray’s safety, I understood hermit crabs caught outside of their shells. Every fiber in my body itched to run, or at least to curl into fetal position before impact.

The sow reached the creek bed sixty feet from us.

To everybody’s surprise, a lingering trace of our scent stalled her like an electric fence. In one fluid motion she pivoted, reprimanded one of the fuzz balls at her heels with a plate-size paw, and blustered up the wash, her cubs trailing as if attached by rubber bands.

Dumbfounded, we tried to coax our heart rates back to normal. The tundra was awash with adrenaline, abuzz with color and detail. The air seemed sweeter, the sun warmer. We flopped down and decompressed, our voices overlapping in disbelief.

Any attempt to fit the scuffle into a quotidian frame of reference failed. We had teetered at the brink. We had passed through moments in which nerves and ligaments could have snapped, trajectories could have changed.

After fifteen minutes—long enough for the sow to traverse several ridges and valleys if she chose to—we continued our hike. Each rock-bear on the hillside appeared ready to trundle. Around the next bend I promptly spotted her again. She was contouring a slope high above. But no, that one looked different. Its legs were the color of freshly cut peat, darker than the body; its size and shoulder hump declared it a male. The boar paid us no attention. He ambled through talus to a razorback ridge, where debris from the mountain swallowed him.

Craving a plot for apparent randomness, we replayed both sightings in search of clues.

Most likely, the sow had first scrapped with the boar. (Male grizzlies kill offspring by rivals to better the chances of their own genes.) She must have been riled up already when she heard us in the wash. Poor-sighted like all bears, she then rushed at the new trespassers to protect her cubs.

As soon as she realized her mistake she bolted in terror, as most grizzlies will upon getting a whiff of people.

By fitting the pieces together, we made sense of the experience. We would revisit it for years to come—embellished, refined, acted out, or on paper—whenever bear behavior cropped up as a topic. In the retelling we construed meaning, and the emphasis slowly shifted from personal, localized lore to link with larger mythologies.

* * * *

Order yours from our bookstore today.